21 August 2022

By Mary Bermingham

mary@TheCork.ie

Michael Collins was shot near Béal na Bláth on 22 August 1922 – Each year there is an oration at ‘The Monument’, Glannarouge West, Bealnablath, Co Cork. This year wasthe centenary so it was be a well-attended event with both the Taoiseach and Tanaiste speaking

Taoiseach’s speech today

Speech by Taoiseach, Micheál Martin T.D., at Béal na Bláth

A Mhéara Chorcaí, a Thánaiste, a Aire Gnóthaí Eachtracha agus Cosanta, a bhaill an Oireachtais, a ionadaithe pobail go léir agus a dhaoine uaisle idir cléir agus tuatha, is pribhléid mhór domsa mar Thaoiseach bheith i láthair anseo tráthnóna inniu ag an suíomh stairiúil ag Béal na Bláth.

Is áit lárnach í seo i stair agus oidhreacht na hÉireann, an suíomh seo in Iarthar Chorcaí ag a bhfuilimid bailithe inniu i gcuimhne ar an laoch agus ar an gaiscíoch Éireannach Mícheál Ó Coileáin a caillleadh anseo céad bliain ó shin.

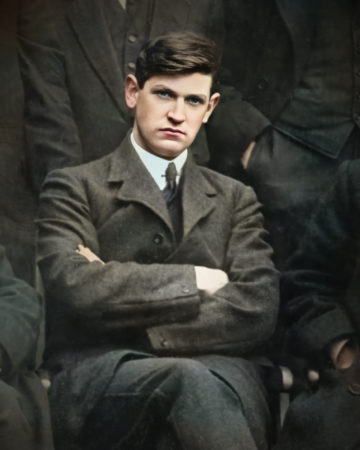

As the first anniversary of Michael Collins’ death approached, a small group gathered in this place to honour a man whose presence was for them still vivid. Close friends from the army as well as his sister stood here in front of a simple wooden cross which one of them had erected. They told brief stories of his life and prayed for him before heading away, deeply affected by their loss.

As we gather today to mark the centenary of his death, we do not have their direct personal connection with him. There is no one here who experienced his charisma, his youthful energy, his booming voice or the strength of his handshake.

Yet this commemoration is an important statement of remembrance and gratitude. It is a mark of our respect for one of the great heroes of Irish history, a man who played an irreplaceable role in securing Irish freedom.

For the political tradition represented by Fine Gael this has long been a place to meet together and to remember a leader who has always provided a special inspiration for them.

However, it is also an important site for all who honour and respect our independence struggle and our democracy.

It is one of the greatest achievements of the last century that different democratic traditions have worked hard to show respect and develop a new understanding of each other.

And we should acknowledge the special role which the Collins family and the Commemoration Committee have played in this over many decades.

Fifty years ago their work led one of my predecessors, Jack Lynch, to designate the Collins homestead as a national monument and to take it into the care of the state. At the same time the Fianna Fáil Minister for Defence Jerry Cronin accepted an invitation to attend this commemoration and laid a wreath on behalf of the government. The invitation to my late colleague Brian Lenihan to speak here twelve years ago marked another important moment.

These and many other generous and open gestures have helped ensure that democratic Irish nationalism has found so much common ground in looking back at our history and the role of our founders in winning independence.

It is my honour and privilege to be here as Taoiseach and as leader of Fianna Fáil to join you in paying tribute to Michael Collins. I am proud that my Department has played a leading role in redeveloping this memorial and making it secure and accessible so that generations to come can continue to visit here to pay their respects.

He is today, as much as he has ever been, an inspiring symbol of how much we can achieve in the face of even the most terrible odds.

In his short 31 years he rose from a modest West Cork home to become a leader in a struggle for independence – a struggle which is responsible for what is today one of the longest continuous democracies in the world.

Everything he achieved in his life came from his great abilities and recognition of his leadership by his peers.

While we all know the outlines of his story and his impact, we should do far more to understand and recognise the brilliance of his service to his country.

A former colleague wrote of him:

“Tall, dark, handsome and strongly built, he had all the dash, initiative, and devilment that fitted him for the role of a great guerrilla warrior. His ability in the handling of finance, as well as his power of speech, were exceptional for a man of his age and education. But that characteristic which stood him in good stead under all conditions was his sense of humour.”

Bhí Mícheál Ó Coileáin múnlaithe go mór ag an bpobal inar rugadh agus tógadh é. Corcaíoch bródúil go smior a bhí sa cheannaire seo. Ní dhearna sé dearmad riamh ar a cheantar féin in Iarthar Chorcaí.

Bhain an Coileánach an méid sin sásaimh as éachtaí agus gaiscí spóirt na tíre seo, bhí baint aige leis an gCumann Lúthchleas Gael agus ón gceangal sin leis an spórt Gaelach, d’fhoghlaim sé luach agus tábhacht na n-eagraíochtaí pobail Éireannacha, a thug seans den scoth do mhuintir na tíre seo uilig a bheith páirteach iontu.

Nuair a bhí an Coileánach críochnaithe lena scolaíocht, thosaigh sé láithreach ag cur le, ag tacú le agus ina theannta sin bhí sé gníomhach i mbunú agus eagrú na n-eagraíochtaí a raibh dlúthbhaint acu lenár n-athbheochan cultúrtha.

Here in West Cork he was immersed in its defining characteristics of self-reliance, determination and compassion. He was shaped by this community and this remained his greatest strength.

After spending 10 years working in London in various clerical jobs, he returned to Ireland in early 1916 and for what became six and a half dramatic years which transformed his country.

Collins was never into hero-worship and he always saw himself as part of a broad movement.

After his service as Aide de Camp to Joseph Mary Plunkett in the GPO, imprisonment was a time for him to reflect on new ways forward.

He was a truly brilliant and creative administrator – something which was recognised by the senior role which he took in the reorganised Sinn Fein. Together with his great friend Harry Boland he was central to the overwhelming victory of the party under the leadership of de Valera in the 1918 election.

That election was a dramatic turning point in our history – and it is at the heart of a profound difference between those who fought the War of Independence and those who have tried to abuse the memory of that struggle.

At the first possible moment, the separatist struggle obtained and retained full democratic legitimacy – a legitimacy which was central to its rapid progress and victory.

Facing down an empire which spanned the world required a lot more than determination and public support – it required a new type and level of organisation never before seen in an independence struggle. At the very heart of this was Michael Collins.Witnessing this, no one could argue with the fact that the Irish people were ready to control their own future.

Collins was a sincere advocate for the Treaty and he was just as committed to trying to prevent the drift towards civil war.

A new generation of historians has looked at the fateful events which led to the civil war using a range of sources never before available.

Their work challenges us to look again, and especially to appreciate just how many efforts were made to bridge the gap between opponents.Collins’ electoral pact and his draft constitution were brave and powerful gestures. They could have worked, but people in London who knew little of our country and showed it little good faith blocked these initiatives and caused immense damage.

And once the major strategic victories of the first two months of the civil war had been achieved by the provisional government there is no doubt that Collins was determined to bring about a rapid end to the conflict.

He did not demonise others because he remembered all he had gone through with them as colleagues and friends. He never celebrated deaths of opponents and showed deep compassion – openly weeping when he heard of the deaths of former colleagues like Cathal Brugha.

And news of his own death is reported to have been met with silence and prayers when it reached republican prisoners.

It is perhaps the greatest tragedy of Collins’ death that it deprived us of our best hope for reconciliation. The bitterness which grew out of the events of the following year showed how much was lost in this place.

We should also do more to remember Collins’ relentless work to try to protect Northern nationalists and his opposition to the partition of our country which had been imposed in 1920.

Throughout the months before his death he continuously challenged London to protect the rights of nationalists in the North. Again and again he tried to stop the systemic violence directed against them.

What he wasn’t willing to do was to take some action which would have led to the sort of scenes later experienced in places like India and Palestine when partition was imposed. The near-complete expulsion of minorities and mass violence defined those partitions and there is every reason to believe that could have occurred here.

Collins acutely felt the outrage of creating a state based on a sectarian headcount – but he also didn’t believe that a new Ireland could be built through a deadly conflict between the two major traditions which share our island.For too long people ignored this fact. The truly historic breakthrough of democratic politics in the Good Friday Agreement gave to our generation, as Seamus Mallon put it, a new dispensation – an opportunity to put sectarianism and artificial division behind us.

That remains our challenge. To do the hard work of moving words to real action on building a shared island – an island where we show respect for our past but we embrace the much harder work of reaching out and respecting each other.

Collins always had a sense of the bigger picture of our complex society and the challenge of bringing it together.When we look back over what has been achieved in the last century I have no doubt that Collins would see a country transformed – an Irish state which has proved to the world that it can achieve great things when it is free to shape its own destiny.

There are those who claim in ever-more passionate speeches that Ireland has achieved nothing in 100 years – and that we are close to being some sort of failed-state. This says more about their cynicism than it does about our country.

We should never forget that in 1922 Ireland was one of the poorest countries in the world. Michael Collins’ father had himself survived one of the most traumatic and deadly famines ever recorded.

With few natural resources. little industry and separated from a significant part of its historic territory, the state which emerged from our revolution faced dramatic hurdles.

And it overcame those hurdles time and time again.

Two million more people live here today than a century ago.

We have recorded one of the highest and most sustained increases in life expectancy of any country – today over 25 years longer than it was in 1922, with reductions in infant and maternal mortality equal to those seen anywhere.

In independent Ireland each new generation has had greater access to education and achieved higher levels of education.

And we have progressed from being one of the most peripheral and poorest countries in the world to the most globally connected of all in terms of trade and employment.

No one doubts that we today face urgent challenges – but those who dismiss the progress we have achieved are denying reality.

And if they fail to respect what our country has achieved, then how can anyone expect that they will protect this progress?Critical for our country is that we have avoided the extremes of the left and right which brought such misery to other countries in the last century.

There has been a lazy tendency to dismiss Irish politics as so-called ‘civil war politics’. However the truth is that after 1923 no party advocating a return to violence has ever won more than 4% of the vote. The parties who have led our governments since then have done so because they have worked to move beyond the civil war and to develop our country in the interests of all.

The centrist, democratic politics which emerged in our country has achieved far more than any other approach could possibly have achieved.

Ireland’s politics has allowed an honest choice between parties which differ on many important issues, but have shared a commitment to democracy, to Ireland’s place in Europe and to creating new opportunities.

This is true to the best and most important element of the tradition founded by Wolfe Tone and which was central to our revolution – that is the commitment to keep evolving, to be open to new ideas and be focused on the needs of today and the future.

We need to do more to confront the new revisionism of those who try to denigrate our country’s achievements and who try to claim legitimacy for violent campaigns waged in the face of the opposition of the Irish people.

We have to give no quarter to their attempts to link themselves to the men and women who fought our revolution over a century ago.

The fact is that our great revolutionary generation radically changed our possibilities and every major piece of progress our country has secured since then has been through centrist and democratic politics.

Our centrist politics has ensured that Ireland has stood for the values of freedom, human rights and democracy in the world.

It is the reason why we joined a union of European democracies, why we are active in promoting the rule of law as a fundamental principle and why we have been resolute in our support for Ukraine as its stands against the imperialist aggression of Russia.And it is this tradition which will enable us to overcome the biggest challenges we face today.

The ability for parties which have different programmes to find a way to work constructively together is central to this government. It is why we can and we will deliver ambitious programmes on the critical issues of housing, climate change and health. It is why we have recovered from the fastest-hitting recession of modern times and have an economy strong enough to help people in the face of rapidly rising international prices.

And this willingness to find common ground is why we have been able to take an approach to remembering even the most difficult parts of our history in an inclusive, respectful and constructive way.

The crowd gathered here today, the presence of representatives of different traditions and the role of Óglaigh na hÉireann in honouring a fallen leader shows how far we have come since the first anniversary of Michael Collins’ death.

In his short 31 years Michael Collins made a deep, lasting and positive impact on our country.

Shaped by the ideals of his community, he devoted his life to his country.

He was a dynamic leader who could both inspire people and, in the middle of a bloody conflict, build a new administration from nothing.

He is a key reason why we have been able to build a country which, while it still faces major challenges, has been transformed for the better.

For this, today, as much as ever before, he deserves our gratitude and he deserves to be remembered as one of the greatest Irishmen to have ever lived.

History

Béal na Bláth or Béal na Blá or Bealnablath or Bealnabla is a small village on the R585 road in County Cork, Ireland. The area is best known as the site of the ambush and death of the Irish revolutionary leader Michael Collins in 1922.

On 22 August 1922, during the Irish Civil War, Michael Collins, Chairman of the Provisional Government and Commander-in-chief of the National Army, was killed in an ambush here by anti-treaty IRA forces while travelling in convoy from Bandon. The ambush was planned in a farmhouse in Béal na Bláth close to The Diamond Bar. Commemorations are held on the nearest Sunday to the anniversary of his death.

A monument was unveiled (2nd August 1924) by WT Cosgrave (1880-1965) and General Eoin O’Duffy (1890-1944) and its inscription reads: “Micheal ÓCoileáin d’éag 22adh Lughuasa [sic] 1922”. It is on a local road which was a dirt road when Collins was shot. Today there is a tarmaced inlet allowing cars to park opposite. A small white pillar marked with a cross, located just to the right of the steps, marks the exact spot where he fell.